What does the Stockholm syndrome have to do with resource security? Read on! 50 years ago, from June 5–16, 1972, the United Nations held its largest ever gathering on development and environment: the Conference on the Human Environment, which convened in Stockholm. It faced tensions: colonies called for self-determination thus challenging the global development doctrine, Cold War ideologies in fierce competition, turmoil over the Vietnam war, and economic expansionists bracing against “Limits to Growth” warnings. Nevertheless, the conference not only led to the establishment of the UN Environment Programme, but also bore a refreshingly clear tagline: “Only One Earth”.

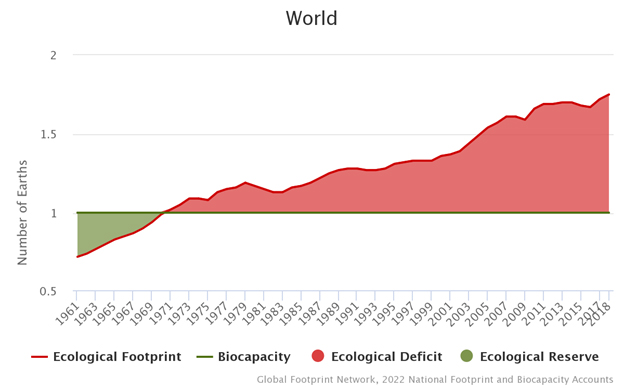

Ironically, that promise had recently been broken. Global overshoot crossed the one-planet mark (figure below) for the first time in the early 1970s, according to the National Footprint and Biocapacity Accounts. This means humanity has been in ecological overshoot for over 50 years, currently using the equivalent of over 1.7 Earths. The persistence of overshoot has now committed the world, with great likelihood, to global warming beyond 1.5°C, as a recent IPCC report confirmed.

50 years of global environment agenda, 50 years of overshoot

These 50-year anniversaries coincide with the 30-year anniversary of the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, which produced the Framework Convention on Climate Change with 166 signatories. Since then, fossil fuel use, the major contributor to greenhouse gases, has doubled. The Kyoto Agreement of 1997 and the Paris Accord of 2015 similarly failed to stop the trend.

The accumulated ecological debt of 50 years of overshoot amounts 19 planet years. This means the ecological debt is as large as what the planet’s ecosystems can regenerate in 19 years. The weight of this debt, which is likely to increase, is starting to reduce economic options. Biodiversity loss, wilder weather, and depleted groundwater are merely inevitable symptoms.

But overshoot itself is not inevitable. It will end, with or without conferences. Since living off depletion is time-bound, our choice is between ending overshoot by design or letting it end by disaster.

Clearly, cities, companies, and countries which do not prepare themselves for the inevitable future – one where we will live off of regeneration rather than depletion – are destroying their own options to fully operate while also exacerbating overshoot. Without making the necessary adjustments which would allow them to thrive in a world of climate change, resource constraints, and massively reduced fossil fuel use, they are not only stealing from humanity’s future but also thwarting their own city, country, or company’s abilities to operate in that future.

Decision-makers who ignore this reality are the enablers of the ecological Ponzi scheme by which future regeneration is stolen through the depletion of today’s natural capital. Surprisingly, their constituencies are still tolerating this lack of foresight, even though the Ponzi scheme is depreciating their own city, company, or country’s future. Protecting the perpetrators is a behavior that eerily reminds us of the Stockholm syndrome[1]. But, if the growing push-back by youth on several continents is any indication, the largely passive attitude of the public towards misguided decision-makers may have begun to erode as people begin to realize that they are being short-changed by those in power.

[1] One year after the Stockholm conference, the host city gained notoriety again: bank robbers took four hostages, who after being kept for 6 days in one of the bank’s vaults, would not testify against either captor in court; instead, they began raising money for their defense. This psychological response wherein a captive begins to identify closely with his or her captors, as well as with their agenda and demands, has become known as Stockholm syndrome.